Archive for the ‘Divorce’ Category

On occasion, a spouse will separate and relocate without telling or notifying the other spouse. Most Court systems have a provision for granting a divorce when you cannot locate your spouse. The Court will usually have a procedure that allows service by publishing and mailing (to the last known address) notice of the divorce. Although the Court may decline to enter substantive orders (such as alimony or child support) without the presence of the other party, the divorce itself will almost certainly be granted.

Every family law case should begin with a strategy. An experienced family law/divorce attorney will listen carefully and work with you to develop and implement a strategy that takes into account the current situation, your goals and objectives, information about your spouse and the realities of the court in which your case will be heard. Are you on the offense or defense? Should you be the first to file or should you let your spouse make the first move? Should you push hard for a negotiated settlement? Or leave matters for the Judge to decide?

Beware of any attorney that has a one size fits all answer – such as “always be the first to file beacuse you are the plaintiff and present your case first” or that “you should surprise and intimidate the other party”.

Cases are different and what may be a successful strategy in one situation could be a disaster in the next. A good family law attorney will move the case in the right direction for you!

It is common for the Courts to issue domestic relations restraining orders to protect parties in divorce and family law cases. Many attorneys and judges feel that they are often given out too easily in these types of situations. However, it is important to remember that the breakup of families is very stressful and emotional. This can often lead to physical violence. Every experienced family law attorney has a horror story to tell and the media is full of stories about people who have been harmed or even murdered in these situations. Therefore, judges tend to err on the side of caution when deciding on whether to issue a domestic relations restraining order.

The standard for obtaining a restraining order may differ slightly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. But it usually involves some fear of imminent potential danger or harm to the party asking for the order. This party should be able to describe specific threats and/or past incidents of violence. Although the Courts are supposed to act in a gender neutral manner, it is much more common to see restraining orders issued against men than women. The actual restraining order itself usually bars or sets limits on contact between the parties and/or their children. If the defendant violates the restraining order, they are subject to criminal penalties and incarceration. The Courts take these violations very seriously and many people have been incarcerated for even minor violations.

If you have a real fear of potential physical harm being perpetrated on you by your spouse or domestic partner, it is very important that you petition the Court for a restraining order to protect you and/or your children. You should also develop a safety plan to protect yourself. The police will serve the restraining order. But they usually won’t station an officer at your residence. In extreme situations, you may need to hide or even relocate to avoid the abusive party.

In 2011, the Massachusetts Legislature passed the Alimony Reform Act (ARA), which made substantial changes to the Masschusetts alimony system, including the implementation of a durational alimony scheme, thereby revising the older system once known as “alimony for life.” Under the old system, the alimony payment period was indefinite in duration, but the new law follows guidelines determined by length of marriage, from 5 years to 20+ years. This raised certain questions and challenges, especially that of alimony judgement pre-ARA (prior to March 1, 2012) as compared with post-ARA judgements. Earlier this year, three notable cases were contested under the new guidelines, questioning whether alimony payors whose divorce judgments were entered prior ARA’s effective date gain the benefit of substantive termination and modification under the new law. These three cases, Doktor v. Doktor, Chin v. Merriot, and Rodman v. Rodman, were all decided on the same day, all with the same answer: “No.”

All three cases were variations of the same concept: the alimony payor requested to end general term alimony payments based on the Massachusetts General Law chapter 208, § 49(f) interpreted as stating that alimony payments shall terminate at the payor’s attainment of full social security retirement age. There were some notable differences between the cases: in Chin v. Merriot, the husband has already reached retirement age at the time of divorce, whereas in both Rodman and Doktor, the paying spouse had attained retirement age after the divorce settlement.

Mr. Chin’s argument hinged on two points: that M.G.L. c. 208, § 49(f) superceded the “uncodified” section 4 of ARA (the provision that, other than durational limits for a marriage of 20 or fewer years, ARA is not in itself a material change of circumstances), and that the cohabitation modification (as his ex-spouse was cohabiting with another man) should retroactively apply. Mr. Rodman’s argument held that a merged alimony agreement such as his merits being treated differently from cases with surviving agreements, and Mr. Doktor argued that his former wife no longer required financial support through alimony. None of these arguments held.

The Supreme Judicial Court instead held that the ARA statute reflects a clear legislative determination that the uncodified sections 4–6 of the ARA override the more payor-friendly substantive sections of M.G.L. c. 208, § 49–55, the only exception being the general term durational limits as defined. The net result? While bad news for pre-ARA payors, the ARA protects payee spouses from abruptly losing their alimony payments when automatic social security retirement age was not obtainable in court. In other words, the SJC’s interpretation of the state legislature’s intent favors the interests of payees over those of payors.

For details of these three cases, please read Doktor v. Doktor, Chin v. Merriot, and Rodman v. Rodman.

For more details of the effects of the Alimony Reform Act, also covering Grounds for Termination of Alimony, Determining the Amount of Alimony to be Paid, and Alimony Modifications, please read Effects of the 2011 Massachusetts Alimony Reform Act, and also Massachusetts Alimony Reform Act of 2011 Law Summary.

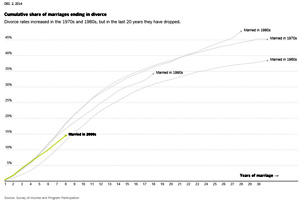

The NY Times, along with several other news sources, recently published an article examining, once again, the “50% Myth” of divorce rates in the USA. I commented on this back in June of 2014 (see US Divorce Rate: The 50% Myth). This is of course a very complex issue with multiple levels of interpretation and analysis from an array of viewpoints both statistical and sociological. However, three main trends are evident:

The NY Times, along with several other news sources, recently published an article examining, once again, the “50% Myth” of divorce rates in the USA. I commented on this back in June of 2014 (see US Divorce Rate: The 50% Myth). This is of course a very complex issue with multiple levels of interpretation and analysis from an array of viewpoints both statistical and sociological. However, three main trends are evident:

1) Divorce rates surged in the 1970s and 1980s, but since have dropped significantly, first in the 1990s and even more so in the 2000s.

2) Couples are marrying later in life: The median age for marriage in 1890 was 26 for men and 22 for women. By the 1950s, it had dropped to 23 for men and 20 for women. In 2004, it climbed to 27 for men and 26 for women.

3) Fewer couples are getting married per capita: many younger couples are living together prior to or instead of marrying, which reduces the divorce rate for couples in their early twenties.

Of course, this is also a simplified view. Much statistical analysis can be applied to these data. For example, one recurring source of the 50% “rule” is that approximately 2.4 million couples marry in a given year, and 1.2 million divorce. 50%, right? But these divorces are not drawn from the same set as the marriages, or, put another way, half of those married in any given year do not divorce in that same year. More significantly, the number of divorces and marriages are taken as totals from the general population, and not from more definitive samples: the percentage of divorces among second (60-67%) and third (70-73%) marriages is much higher than among marriages that don’t end in divorce, skewing the numbers.

A more accurate approach would be to calculate how many people who ever married subsequently divorced. Calculated in this manner, the US divorce rate has never exceeded 41 percent, and in fact is currently dropping. According to the 2001 survey of the Fertility and Family Branch of the Census Bureau, the rate of divorce for men between 50 and 59 was 41% and for women between 50 and 59 was 39%.

In any case, divorce is a real consideration in marriage, ultimately affecting close to 4 in 10 couples. If you find yourself in the 40 percentile, consider consulting a qualified divorce attorney to examine your situation and the best way forward.

Most states have child support guidelines. These are formulas that the courts of a particular state will use to determine a child support amount. While the elements of the formula will vary by state, the most important factors are the incomes of the parties and number of children. The formulas will usually also include some type of adjustment for health insurance, child care costs and sometimes other expenses.

Most states have child support guidelines. These are formulas that the courts of a particular state will use to determine a child support amount. While the elements of the formula will vary by state, the most important factors are the incomes of the parties and number of children. The formulas will usually also include some type of adjustment for health insurance, child care costs and sometimes other expenses.

Judges are usually empowered with discretion to vary from these formulas. Depending upon the particular judge and jurisdiction, this may or may not happen. If you think that your particular situation merits a variance from the formula amount, you should thoroughly discuss the matter with your attorney and decide whether it is worthwhile to present your arguments to the Court. While the Court may not grant your entire request, the Judge may make some type of favorable adjustment to the amount indicated by the formula.

Common arguments to vary child support from state child support guidelines include tax issues, unreported income, large and unusual business expenses, prior child support orders, large and unusual personal expenses of a parent, children’s educational expenses, time spent at college, health and medical issues, other ways in which the non-custodial parent is supporting the child(ren), the amount of time the child(ren) are in the care of a particular parent, unusual travel expenses for visitation with the children, imputation of income; and the interplay of alimony and child support. Judges also usually have the discretion to determine who can claim any income tax exemptions and/or tax credits associated with the children (or at least adjust the child support amount to compensate for these exemptions and/or tax credits).

An experienced divorce attorney will be able to evaluate your particular situation, tell you the particular tendenices of an individual judge and determine what types of arguments might be favorably received by the Court.

There is no “one size fits all” answer as to whether you should be the first to file for divorce. There are various reasons why it may or may not be to your strategic advantage to be the first to file. You might even think of it in sports terminology: Do I play offense or defense?

There is no “one size fits all” answer as to whether you should be the first to file for divorce. There are various reasons why it may or may not be to your strategic advantage to be the first to file. You might even think of it in sports terminology: Do I play offense or defense?

Some of the reasons that you may want to file first include:

1) A likely decision by the Court that is favorable to what you are seeking;

2) A need to finalize the divorce as soon as possible to allow for remarriage;

3) A psychological need to end the marriage as soon as possible in order to move on with your life;

4) A need to send a clear and unequivocal message to your spouse that “the marriage is over and that there is no hope for reconciliation”;

5) A need to force your spouse to vacate the marital domicile;

6) A need to put into place orders to protect marital assets;

7) A need to obtain orders for alimony or child support;

8) A need to obtain an order for child custody or to ask that you be allowed to remove the children from the current state of residence;

9) A need to expedite the sale of a marital home or other marital property.

Conversely, some of the reasons that you may not want to be the first to file for divorce include the following:

1) A likely decision by the Court that would not be favorable to you (and the possibility that you might be able to arrive at an agreement with your spouse that would be signifcantly better for you than what the Court would order in your circumstances);

2) Situations where the current support being provided by your spouse is more than you could reasonably expect the Court to order;

3) When your spouse is gravely ill and you want to preserve an interest in their portion of the marital estate;

4) Situations where your spouse is in a “hurry” to finalize a divorce (either for psychological reasons or for a desire to remarry) and you gain a tactical advantage in negotiating an agreement from their haste to resolve the matter as quickly as possible;

5) When you believe the marriage is still salvageable.

With the exception of the analysis of your particular situation and likely outcomes by the Court, most of the above is fairly straightforward. An experienced divorce attorney that understands the tendencies of the Courts and judges in your particular jurisdiction should be able to study your particular situation, perform this analysis and advise you as to your best course of action.

There is a fine line in divorce and family law between assertively pressing your case and literally fighting about each and every issue all the time. Recently, I was asked by a family member to refer her to a good divorce attorney (both parties were too close personally to represent her myself). I considered several colleagues who are very competent, but settled on giving her the names of two lawyers in particular. In discussing these choices with the family member, I told her that in my opinion there’s a fine line between assertively and aggressively representing a client and being so obnoxious and aggressive that an attorney only makes the situation worse for the client and the family. In any particular case, this line can be easily crossed. I thought these two individuals wouldn’t back down, but they also weren’t likely to create conflicts unnecessarily.

There is a fine line in divorce and family law between assertively pressing your case and literally fighting about each and every issue all the time. Recently, I was asked by a family member to refer her to a good divorce attorney (both parties were too close personally to represent her myself). I considered several colleagues who are very competent, but settled on giving her the names of two lawyers in particular. In discussing these choices with the family member, I told her that in my opinion there’s a fine line between assertively and aggressively representing a client and being so obnoxious and aggressive that an attorney only makes the situation worse for the client and the family. In any particular case, this line can be easily crossed. I thought these two individuals wouldn’t back down, but they also weren’t likely to create conflicts unnecessarily.

Unfortunately, there are many overly aggressive lawyers, and some members of the public think this is a great thing. The reality of the situation is that most family law and/or divorce cases settle in the end and only a small percentage go to trial. If there are children involved, the parties almost always will have to maintain some type of working relationship after the litigation. In many areas of family law, there is room for win-win arrangements that accrue to the benefit of both parties. If the attorneys are constantly battling and fail to really communicate the opportunities for these arrangements are lost.

If the matter does go to trial, there are usually limited areas of disagreement and it is also helpful if the parties can agree on some issues if only for the reason of limiting costs.

Some attorneys promote the image of being “aggressive” – which often means they are looking to run up a bill and usually leave their clients angry and their families and children in ongoing turmoil. No matter how angry or upset you are with your spouse, don’t make the mistake of hiring such an attorney.

This is not to say that your attorney should be a passive wallflower. But, you should always keep in mind that there is a fine line and that your attorney’s job is to do what’s best for you, the client. A good family law attorney willl be assertive and aggressive in representing your interests, but will choose his (and your) battles wisely.

In a divorce, fairly dividing the relatively small value items of personal property (all that junk in the house) is an area where the legal system often performs poorly. Oftentimes, the monetary value of these items doesn’t justify the legal costs incurred in their retrieval. In Court, the division of these types of items is usually the last thing to be addressed. Every attorney has a horror story to tell about the case where many torturous hours were spent between two litigants arguing over every small piece of furniture, silverware and tools.

In a divorce, fairly dividing the relatively small value items of personal property (all that junk in the house) is an area where the legal system often performs poorly. Oftentimes, the monetary value of these items doesn’t justify the legal costs incurred in their retrieval. In Court, the division of these types of items is usually the last thing to be addressed. Every attorney has a horror story to tell about the case where many torturous hours were spent between two litigants arguing over every small piece of furniture, silverware and tools.

A spouse who is no longer residing in the marital home (either because they voluntarily left or they were put out by the Court) is at a distinct disadvantage in identifying, dividing and retrieving these types of items. If you can divide these small items between yourself and your spouse without the involvement of the Courts you will save a great deal of expense and hassle. If you cannot do this on your own, start by preparing a complete and comprehensive list of everything that you want to get back. Don’t wait to go to Court. Show that you are serious about retrieving these items and that this is important to you by having your attorney forward the list to your spouse’s attorney before you go to Court. Don’t wait for the last minute and be faced with a decision as to whether to settle the case or fight for the bed! Also, don’t tie up valuable attorney time by wasting time on low value items.

Be flexible and be willing to trade-off different items. Don’t ask for all the televisions in the house – but try to get at least one. Try to get something in each class of item – a vcr, a stereo, a dvd player, some silverware, plates, etc. This way you won’t have to start from scratch. The same with furniture – divide it room by room. If you don’t have space for an item or it will be difficult to move, seriously consider whether you really want it back. Do you really need a lawnmower and garden tools when you’re moving into an apartment? If you are not allowed back in the house because of a restraining order – ask to inventory the items in advance in the company of a police officer (called a detail – and be prepared for a cost – usually a minimum of 3-4 hours). If you have pictures with sentimental value to divide and cannot agree, offer to split the costs of making a second set (this is usually what judges will do anyway). Decide what you really need and what you can live without. Lastly, seize the opportunity to reduce the clutter in your life and get a fresh start!

When thinking of divorce, one of the most common questions that arise is “What will happen to my House if I get divorced?” Courts usually have the power to order the sale of the marital home. However, the status of the marital home during and after a divorce depends on whether there are children residing in the home, whether one party can “buy out” the interest of the other, or whether there are other assets to offset the equity in the home.

When thinking of divorce, one of the most common questions that arise is “What will happen to my House if I get divorced?” Courts usually have the power to order the sale of the marital home. However, the status of the marital home during and after a divorce depends on whether there are children residing in the home, whether one party can “buy out” the interest of the other, or whether there are other assets to offset the equity in the home.

The first consideration is usually whether minor children are residing in the home. If there are children living in the house and it has been their home for a period of time, the Courts are usually very reluctant to order the home sold (absent extenuating circumstances, such as a severe mortgage delinquency or pending foreclosure) and the children uprooted. This is especially true earlier in a divorce action. Usually, the Court will give the party residing in the house a chance to come up with a plan to make the mortgage payments and retain the property. Judges would much rather give the parties the time to craft their own plan and on their own terms as to the disposition of the marital home than enter an order for its sale. If the case goes to trial and the Judge is forced to make a decision as to the sale of the marital home, it is likely that the Court will still not order the marital home sold until the children are emancipated. It is usually said that the non-resident spouse (usually the father) has an “illiquid asset” when there are children residing in the house. However, it is possible that the Court would offset the equity in the marital home against the value of other assets (such as retirement assets).

When there are no minor children residing in the house, the immediate sale of the marital home is much more likely. This is especially true if the equity in the marital home represents the primary marital asset or bulk of the marital assets. If there are substantial other assets, they can often be utilized to offset some or all of the equity in the marital home. Although judges are usually amenable to giving either spouse the opportunity to “buy out” the other spouse’s interest in the home, they are also cognizant of the fact that this is often impractical.

If a “buy out” is to happen, the equity in the home must be established. Certified real estate appraisers are often utilized. The appraisal(s) are then coupled with a formula (such as 50-50) to establish each spouse’s interest. When the home is sold, the valuation is usually straightforward. Assuming an arm’s length transaction, the value is the sales price.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that in a soft real estate there is a greater reluctance to sell real estate. Even though the parties agree to sell the marital home or the court orders it sale, the property may remain on the market unsold for an extended period of time.

Since the economic downturn of 2008, many have reported that the divorce rate is slightly down because of the economy. This is true. However, the Courts and attorneys that practice family law are busier than ever because people are reopening old support orders and filing for contempts as jobs are lost, incomes decrease, and asset values decline. Additionally, cases are being fought and litigated much harder and more aggressively as parties fight over an ever decreasing pie. One of the effects of the changing economy was the Massachusetts 2011 Act Reforming Alimony in the Commonwealth (read more).

Since the economic downturn of 2008, many have reported that the divorce rate is slightly down because of the economy. This is true. However, the Courts and attorneys that practice family law are busier than ever because people are reopening old support orders and filing for contempts as jobs are lost, incomes decrease, and asset values decline. Additionally, cases are being fought and litigated much harder and more aggressively as parties fight over an ever decreasing pie. One of the effects of the changing economy was the Massachusetts 2011 Act Reforming Alimony in the Commonwealth (read more).

For some people (usually men), this is a great time to file for divorce. If you are already paying alimony or child support you might even consider filing for a modification. Alimony and child support orders are almost always based on current income. If you are unemployed or your income has decreased substantially, alimony and/or child support should reflect this and you should be paying less. Many people fail to have the Courts reduce their support obligation when they lose their jobs or their income decreases (it doesn’t automatically go down – you must go back to Court!) and end up with large arrearages. If your income subsequently increases, the party receiving the support will have to refile and bring you back to court to increase the support. Many (if not most) support recipients fail to do this. They usually don’t even know that the income of the payor has increased! I have seen many cases where support orders are based on incomes that are a fraction of the payor’s current income.

This becomes especially important in alimony cases. Depending upon the judge, alimony may be particularly difficult to change. If the alimony order was based on a period during which the payor’s income was low, it may be very difficult for the recipient spouse to obtain an increase.

Lastly, the value of assets that are usually retained by men in property settlements (such as a family business or stock options) may be temporarily depressed in a slow economy and therefore the wife would receive a smaller share of other assets to accomplish property division.